~

- Report by the United Nations Commission of Inquiry released Monday

- Testimony by North Koreans refugees presents bleak portrait of human rights in regime

- Witnesses tell of inhuman treatment, arbitrary detention, abuse and starvation

- Pyongyang has refused to participate in the investigation, condemning it as a “charade”

(CNN) — The testimonies, one after another, have been damning, disturbing and, at points, excruciating.

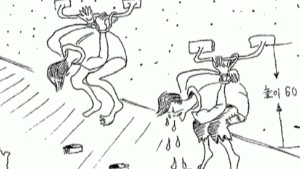

A North Korean prison camp survivor told of a pregnant woman in a condition of near-starvation who gave birth to a baby — a new life born against all odds in a grim camp. A security agent heard the baby’s cries and beat the mother as a punishment.

She begged him to let her keep the baby, but he kept beating her.

With shaking hands, the mother was forced to pick up her newborn and put the baby face down in water until the cries stopped and a water bubble formed from the newborn’s mouth.

U.N. report details abuse in North Korea

U.N. report details abuse in North Korea

North Korea: UN report a political plot

North Korea: UN report a political plot

Amnesty: Victims need to come forward

Amnesty: Victims need to come forward

U.N. chair: Witness evidence powerful

U.N. chair: Witness evidence powerful

UN hears story of North Korean torture

UN hears story of North Korean torture

It’s just one example of the kind of testimony heard during an 11-month inquiry into alleged violations of human rights in North Korea, and documented in a report released by the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights on Monday.

The commission concluded that North Korea has committed crimes against humanity. The commission investigated issues regarding the right to food, prison camps, torture and inhuman treatment, arbitrary detention, discrimination, freedom of expression, the right to life, freedom of movement, and enforced disappearances, including abductions of other citizens.

The panel reported a stunning catalog of torture and the widespread abuse of even the weakest of North Koreans that reveal a portrait of a brutal state “that does not have any parallel in the contemporary world.”

It remains to be seen what impact the report might have and whether China, a member of the U.N. Security Council and staunch ally of North Korea, will block action seeking human rights redress.

Collection of evidence

Since its creation last year, the commission of inquiry has examined satellite imagery, evidence and testimonies from more than 100 victims, witnesses and experts regarding North Korea. Some of the testimonies were held confidentially because of protection concerns for family still remaining in North Korea.

International attention on North Korea has previously focused on halting its nuclear weapons program, but, in response to increasingly detailed reports of human rights abuses emerging from the isolated state, the U.N.’s Human Rights Council elected in March to establish the commission.

For many North Koreans who testified, it was an acknowledgment of the sufferings they endured living and fleeing the regime. North Korea is said to practice “guilt by association” — punishing members of a person’s family and succeeding generations for one person’s perceived misdeeds.

Pyongyang has refused to cooperate with the investigation and rejects the commission’s validity. The commission of inquiry requested access to North Korea and also invited its authorities to examine its evidence and also contribute in the process.

In May 2013, North Korea sent a letter saying it “totally and categorically rejects the Commission of Inquiry” and has not answered subsequent letters, said Michael Kirby, the chair of the U.N. Commission of Inquiry.

The commission comprises three appointees, chaired by Kirby, a former Australian High Court judge, along with Sonja Biserko of Serbia and Marzuki Darusman of Indonesia.

Through its official news agency, KCNA, North Korea in August condemned the hearings as a “charade” to “hear testimonies from human scum.”

A life in imprisonment

Throughout public hearings held in Seoul, Tokyo, London and Washington, D.C., former North Koreans told of torture and imprisonment for watching soap operas or trying to find food to sustain their families. Many of them ended up in prison camps for crossing the border to China or for having family members who were suspect to the regime.

Jee Heon A, former prisoner

The North Korean prison camps have survived twice as long as Stalin’s Soviet gulags and much longer than the Nazi concentration camps.

One witness said that young male inmates in North Korean prison camps became so desperate for food they would eat live worms or snakes caught in the field to feel something in their stomachs.

“Because we saw so many people die, we became so used to it,” one prison camp survivor told the commission. “I’m sorry to say that we became so used to it that we didn’t feel anything. In North Korea, sometimes people on the verge of dying would ask for something to eat. Or when somebody died we would strip them naked and we would wear the clothes. Those alive have to go on, those dead, I’m sorry, but they’re dead.”

Jee Heon A told the commission of her time in a North Korean prison. She was sent there after being repatriated from China. She befriended a young girl, named Kim Young Hee and became like a sister to her. While they were forced to work in the fields, they were looking for a type of grass to eat, as their prison rations were not enough.

“We finished our work and we were about to pick up this grass or the plant that we knew we could eat,” Jee told the commission. “And then the guards saw us, and he came running and he stepped on our hands and then he brought us to this place and he told us to kneel.”

They were forced to eat the grass along with the root and the soil as punishment. Kim became increasingly sick with diarrhea after eating the soil.

“There was nothing I could do,” Jee said. “I could not give her any medicine. And when she died, she couldn’t even close her eyes. She died with her eyes open. I cried my heart out.”

She wrapped Kim’s body in a plastic bag and the other prisoners buried her and about 20 other bodies from the prison on a hill.

Orphaned and homeless in North Korea

“We covered the hole with clumped and frozen earth, but after a week when we went to the tomb, it was gone, the bodies were not there. We felt strange when we were going up that hill. We later found out that the old man who was guarding the place had his dogs eat the bodies. He raised five dogs and the dogs were eating the heads and the body parts of dead bodies.”

This is the reality of the North Korea prison, Jee stated.

She ended her testimony saying: “I am embarrassed, I am ashamed to be here. There are people dying but because I was so desperate to make ends meet for myself, I was not able to help and I’m guilty of it.”

“I live like a prisoner, the reason for my living, the reason that I had to come to South Korea, in addition for my own freedom, is to survive and live on behalf of those who didn’t make it. People died for no reason. To help their souls rest in peace I have to be accountable for their lives.”

http://www.cnn.com/2014/02/16/world/asia/north-korea-un-report/

~

~

Ahn Myong-Chol witnessed many horrors as a North Korean prison camp guard, but few haunt him like the image of guard dogs attacking school children and tearing them to pieces.

Ahn, who worked as a prison camp guard for eight years until he fled the country in 1994, recalls the day he saw three dogs get away from their handler and attack children coming back from the camp school.

“There were three dogs and they killed five children,” the 45-year-old told AFP through a translator.

“They killed three of the children right away. The two other children were barely breathing and the guards buried them alive,” he said, speaking on the sidelines of a Geneva conference for human rights activists.

The next day, instead of putting down the murderous dogs, the guards pet them and fed them special food “as some kind of award,” he added with disgust.

“People in the camps are not treated as human beings… They are like flies that can be crushed,” said Ahn, his sad eyes framed by steel-rimmed glasses.

The former guard is one of many defectors who provided harrowing testimony to a UN-mandated enquiry that last week issued a searing, 400-page indictment of gross human rights abuses in North Korea.

After fleeing the country two decades ago, Ahn worked for years at a bank in South Korea but gradually got involved in work denouncing the expansive prison camp system in the isolated nation.

Three years ago, he quit his bank job to dedicate all his time to his non-governmental organisation, Free NK Gulag.

“It’s my life’s mission to spread awareness about what is happening in the camps,” he said.

There are an estimated 80,000 to 120,000 political prisoners in North Korea, a nation of 24 million people.

Ahn, who today is married with two daughters, knows all too well the brutal mentality of the camp guards.

When he, as the son of a high-ranking official, was ushered onto the prestigious path of becoming a guard in 1987, he says he was heavily brainwashed to see all prisoners as “evil”.

- ‘Horrors still happening’ –

At his first posting at camp 14, north of Pyongyang, he was encouraged to practice his Tae Kwon Do skills on prisoners.

And he recalls how guards were urged to shoot any prisoner who might try to escape.

“We were allowed to kill them, and if we brought back their body, they would award us by letting us go study at college,” he said.

Some guards would send prisoners outside the camp and kill them as escapees to gain access to a college education, he added.

Ahn said he had beaten many prisoners but said that, to his knowledge, he had never killed any of them.

Although he witnessed numerous executions, starving children, and the effects of extreme torture, it was not until he was promoted to be a driver, transporting soldiers back and forth between camps, that he began to question the system.

During his travels he sometimes struck up conversations with prisoners and was astonished to find that “more than 90 percent” of them said they had no idea why they were in the camp.

Ahn had stumbled across North Korea’s system of throwing generations of the same family into prison camps under guilt-by-association rules.

He got a taste of that rule himself. On leave in 1994, he returned home to find that his father had committed suicide after making some drunken, negative remarks about the country’s leadership.

Ahn’s mother, sister and brother were detained and likely sent into camps, although he is not sure what became of them.

Though Ahn returned to work, he feared he too would be dragged off. So he drove his truck to the shores of the Du Man River and swam across to China, having to dump the heavy weapons he was carrying to avoid drowning.

Once he got involved in the NGO work in South Korea, he was uneasy about meeting former prisoners who had also managed to defect, like Chol Hwan Kang.

Kang was sent to Camp 15 — where Ahn once served — with his whole family when he was nine and spent 10 years there to repent for the suspected disloyalties of his grandfather. Ahn remembered him from his time as a guard there.

But Kang, like most survivors, understood he had not chosen his job and had accepted his plea for forgiveness.

“He met me with a gentle handshake,” Ahn said.

Last week’s UN report was vital to spreading awareness about the reality of the camps, Ahn said, comparing what is happening there to the Soviet-era Gulags.

“The difference is that in North Korea we are still talking in the present tense. These horrors are still happening,” he said.

[Image via Agence France-Presse]